Dearer Funding Will Hurt

The Japanese debt market made the news over the last few days as its anchored much higher inflation matched poorly with government funding needs. Rates spiked on the long end and utterly changed the outlook for bearer of long term debt assets. The Japanese 10y at 1.16% now trades 90bp above the going rate of early 2024.

Japan is not alone. The $10y is up 60bp over the same period, the French 10y gained 70bp and the US gained 60bp of late. The farther the term, the larger the spread widening.

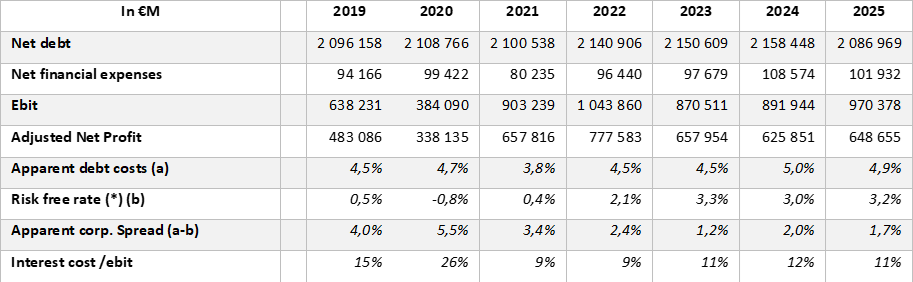

In that light we dusted off a short report written 6 months ago about the rising financing costs for European corporates. It starts with the following table reflecting on the actual interest paid by European issuers (leaving Banks and Insurance alone).

Corporates financing costs so far little impacted by higher risk free rates

(* 66% 10y Euro swaps, 33% 10y Gilts)

The risk free rate (computed as 67% € and 33% GBP) has been rising since the lows of 2020, based on the 10y metrics. The apparent interest rate has not, so that the spread effectively paid on existing layers of debt has declined from 4% to less than 2%.

The obvious question is whether a 1.7% corporate spread can survive perceived rising risks. Indeed the world is on a risk ‘reset’ as the Trump initiatives force corporates out of their torpor.

We clearly think that lenders will want more by way of spreads when the old layers of funding are up for a roll. The cheapest funding, i.e. the free money in the midst of Covid will probably have been repaid by the end of the current year.

If one assumes that the debt markets are the driving party (which we believe), another 100bp to 150bp widening in the corporate spread is bound to become visible in 2025-2026 P&Ls, assuming an average 5-year roll. +100bps is worth c. €22bn in post-tax earnings or 3% erosion of earnings expectations. That pressure will come on top of trade frictions, a weakening $ and bouts of wage inflation here and there.

The above comment assumes that long rates stay where they are but their own fluctuations will determine the level of the required spread. The worse that could happen is that issuers face flattening GDPs with rising funding costs.

In all it seems likely that the P&Ls of larger European corporates have yet to experience the full cost of the rate rises (started in early 2022) which continue unabated on the long end of the curve. That interest bill will end up being painful.

Japan is not alone. The $10y is up 60bp over the same period, the French 10y gained 70bp and the US gained 60bp of late. The farther the term, the larger the spread widening.

In that light we dusted off a short report written 6 months ago about the rising financing costs for European corporates. It starts with the following table reflecting on the actual interest paid by European issuers (leaving Banks and Insurance alone).

Corporates financing costs so far little impacted by higher risk free rates

(* 66% 10y Euro swaps, 33% 10y Gilts)

The risk free rate (computed as 67% € and 33% GBP) has been rising since the lows of 2020, based on the 10y metrics. The apparent interest rate has not, so that the spread effectively paid on existing layers of debt has declined from 4% to less than 2%.

The obvious question is whether a 1.7% corporate spread can survive perceived rising risks. Indeed the world is on a risk ‘reset’ as the Trump initiatives force corporates out of their torpor.

We clearly think that lenders will want more by way of spreads when the old layers of funding are up for a roll. The cheapest funding, i.e. the free money in the midst of Covid will probably have been repaid by the end of the current year.

If one assumes that the debt markets are the driving party (which we believe), another 100bp to 150bp widening in the corporate spread is bound to become visible in 2025-2026 P&Ls, assuming an average 5-year roll. +100bps is worth c. €22bn in post-tax earnings or 3% erosion of earnings expectations. That pressure will come on top of trade frictions, a weakening $ and bouts of wage inflation here and there.

The above comment assumes that long rates stay where they are but their own fluctuations will determine the level of the required spread. The worse that could happen is that issuers face flattening GDPs with rising funding costs.

In all it seems likely that the P&Ls of larger European corporates have yet to experience the full cost of the rate rises (started in early 2022) which continue unabated on the long end of the curve. That interest bill will end up being painful.

Subscribe to our blog

If one is not inclined to cut a bit of each A&D holding, and is intent on retaining all-weather Airb...